Let’s be honest — whenever someone moans that “technology is ruining music,” they usually mean their music. What they’re really saying is that the version of music they grew up with — the one that involved guitars, microphones, maybe a four-track — is being replaced by kids tapping out beats on laptops, using software they can barely pronounce.

But here’s the thing: music has always been shaped by technology. In fact, it’s hard to separate the two. From bone flutes to digital streaming, every breakthrough has transformed not just how music sounds, but how we write it, play it, share it — and even how we feel about it.

So no, the machines didn’t just take over recently. They’ve been here the whole time.

- Before the machines: music’s first tech experiments

- The first real disruption: capturing music for later

- The microphone: small device, huge change

- The amplifier: from polite to powerful

- The studio becomes an instrument

- Synthesizers: when sound went synthetic

- MIDI: the unsung hero of modern music

- DAWs: the studio moves into the bedroom

- The MP3 and the disintegration of the album

- Virtual instruments: orchestras in your laptop

- The machines get clever: here comes AI

- So — where does this all leave us?

- Learn music technology

Before the machines: music’s first tech experiments

Long before electricity, before cables and compressors and blinking red lights in the studio, there were other breakthroughs. Rudimentary, but revolutionary in their time.

The human voice was the original instrument. Then someone figured out that hitting a hollow log made a sound that echoed in your chest — drums. The flute — arguably the first melodic instrument — emerged when someone drilled holes into a bear’s leg bone 40,000 years ago and blew into it. Crude? Yes. But it worked.

As humans got a bit more civilised (and had a bit more free time), we invented the lyre, the harp, and eventually the lute — early stringed instruments that let you play notes together. Suddenly, we had harmony. The harpsichord arrived during the Renaissance and added a sense of ceremony, but no matter how fancy it looked, it couldn’t whisper or roar. It was all one volume — plucked, not struck.

As humans got a bit more civilised (and had a bit more free time), we invented the lyre, the harp, and eventually the lute — early stringed instruments that let you play notes together. Suddenly, we had harmony. The harpsichord arrived during the Renaissance and added a sense of ceremony, but no matter how fancy it looked, it couldn’t whisper or roar. It was all one volume — plucked, not struck.

That all changed around 1700, when Bartolomeo Cristofori — tired of this lack of dynamics — built the piano, which finally let musicians play soft and loud, based on how they touched the keys. It was like inventing emotional range overnight.

Then came the guitar. Born of folk traditions, refined in 19th-century Spain, and eventually made affordable and portable enough to be slung over the backs of buskers and teenagers everywhere. It went from parlour rooms to protest marches to pop charts — and when someone plugged it in, the world changed.

These weren’t just instruments. They were all technological leaps — tools that expanded what music could be.

But the real explosion of music technology — the kind that introduced recording, electricity, data, and machines — was still to come.

The first real disruption: capturing music for later

Before the late 19th century, music was an event. You had to be there. It happened in a room, with people, and when it was over, it was gone. A performance was a moment in time. You could hum the tune afterwards, maybe try to play it from memory, but the moment itself had passed.

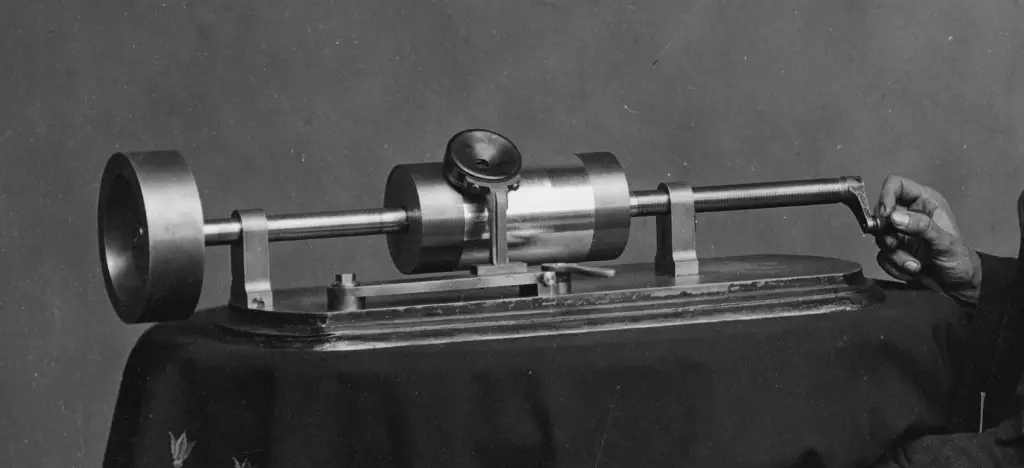

That all changed in 1877, when Thomas Edison, tinkering as he often did, built the phonograph.

It wasn’t even invented for music — Edison thought it would be useful for taking dictation or recording last words. But it worked: a needle etched soundwaves into tinfoil on a rotating cylinder, and another needle played them back. It was scratchy and barely audible, but for the first time in human history, sound could be stored. Not just music — any sound.

It wasn’t even invented for music — Edison thought it would be useful for taking dictation or recording last words. But it worked: a needle etched soundwaves into tinfoil on a rotating cylinder, and another needle played them back. It was scratchy and barely audible, but for the first time in human history, sound could be stored. Not just music — any sound.

About ten years later, Emile Berliner improved on it with the gramophone, swapping the cylinder for a flat disc. Easier to press. Easier to store. Easier to mass-produce. The record was born.

About ten years later, Emile Berliner improved on it with the gramophone, swapping the cylinder for a flat disc. Easier to press. Easier to store. Easier to mass-produce. The record was born.

And with it, the entire concept of a recording artist. Now a musician didn’t have to tour to be heard. They could perform once, press a few thousand copies, and let the music travel without them. Music stopped being fleeting — and became physical.

This wasn’t just a shift in convenience. It fundamentally altered the relationship between musicians and their audience. Music could now be owned. Collected. Replayed until the grooves wore out.

💡 ARTMASTER TIP: The Grammy Awards began in 1959 as the music industry’s attempt to create its own version of the Oscars. Find out more in our article on how the Grammys are won.

The microphone: small device, huge change

If the phonograph preserved sound, the microphone refined it. Early recordings used massive horns to capture volume. Singers had to bellow, entire bands had to huddle around a diaphragm that barely picked up bass frequencies. It was crude and brutal, and if you didn’t sing like a foghorn, forget it.

But in the 1920s and ‘30s, new microphone technologies — ribbon mics, condenser mics — changed the game. Suddenly, you didn’t need to shout. You could sing softly, subtly, even sensually. A crooner like Bing Crosby didn’t just sound good on a mic — he only made sense on a mic. The technology reshaped the art form.

But in the 1920s and ‘30s, new microphone technologies — ribbon mics, condenser mics — changed the game. Suddenly, you didn’t need to shout. You could sing softly, subtly, even sensually. A crooner like Bing Crosby didn’t just sound good on a mic — he only made sense on a mic. The technology reshaped the art form.

The microphone also did something that’s easy to overlook: it turned performance into presence. It brought the voice closer to the ear, made it intimate. You weren’t hearing someone perform in a hall — you were hearing someone speak directly to you. And with that, a new style of performance was born — quieter, closer, more personal.

💡 ARTMASTER TIP: The mic gave singers a new kind of power — not volume, but intimacy. It let voices soften, whisper, connect. If you're curious how to tap into that kind of expressive control yourself, start with Can anyone learn to sing?

The amplifier: from polite to powerful

Recording wasn’t the only area where things got louder. In live music, performers faced a similar problem: how do you make sure the audience at the back hears the music? Enter the amplifier.

By the 1930s, electric amplification wasn’t new—public address systems already existed—but what changed music was the realisation that you could plug in instruments, not just microphones. The electric guitar was one of the first instruments to fully embrace amplification, and not just to be heard, but to sound different. Add a little overdrive, and suddenly you’ve got growl, sustain, character.

By the 1930s, electric amplification wasn’t new—public address systems already existed—but what changed music was the realisation that you could plug in instruments, not just microphones. The electric guitar was one of the first instruments to fully embrace amplification, and not just to be heard, but to sound different. Add a little overdrive, and suddenly you’ve got growl, sustain, character.

The electric guitar wasn’t just a louder acoustic guitar. It was a new voice entirely. Think Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly, and later, Jimi Hendrix, who didn’t just play through amps—he played the amp itself, using feedback and distortion like a painter uses colour.

The amplifier gave us volume, yes—but more than that, it gave us attitude. It allowed music to be brash, confrontational, and loud enough to be impossible to ignore.

💡 ARTMASTER TIP: Amplification didn’t just make guitars louder — it made them iconic. Thinking of picking one up yourself? Here’s how long it really takes to learn guitar, and what to expect along the way.

The studio becomes an instrument

By the 1950s, another shift was underway — this time inside the studio. Before that, recordings were made like live performances: everyone gathered in a room, and they played it straight. One take. One mic. Try not to sneeze.

Then magnetic tape arrived, and with it, the ability to edit. Now you could splice takes together, correct mistakes, try things out. You didn’t have to get it right the first time—you could build the perfect performance brick by brick.

Then magnetic tape arrived, and with it, the ability to edit. Now you could splice takes together, correct mistakes, try things out. You didn’t have to get it right the first time—you could build the perfect performance brick by brick.

And then came multitrack recording, pioneered by — you guessed it — Les Paul, who by this point had already helped invent the solid-body electric guitar. With multitrack tape, musicians could record instruments separately and layer them later. Drums on one track, bass on another, vocals on a third. Suddenly, the studio wasn’t just capturing music — it was shaping it.

By the time The Beatles were recording Sgt. Pepper, they weren’t a band in a room — they were composers in a laboratory. Tapes ran backwards. Effects were printed live. Instruments were recorded at half-speed. Nothing was off-limits. The studio had become part of the band.

💡 ARTMASTER TIP: Multitrack recording turned the studio into a creative playground — and now, that playground fits on your laptop. If you’re ready to start making music at home, our beginner’s guide to home production has everything you need.

Synthesizers: when sound went synthetic

If amplification let music shout, synthesizers let it speak a whole new language.

In the 1960s, a genial engineer named Robert Moog introduced a machine that looked more like a switchboard than an instrument. It didn’t have strings, reeds, or anything to blow into. It generated sound using voltage — raw electricity shaped by dials, oscillators, and patch cables. And for the first time, music wasn’t bound by the physical properties of wood, metal, or skin. You could make sounds that had never existed before.

In the 1960s, a genial engineer named Robert Moog introduced a machine that looked more like a switchboard than an instrument. It didn’t have strings, reeds, or anything to blow into. It generated sound using voltage — raw electricity shaped by dials, oscillators, and patch cables. And for the first time, music wasn’t bound by the physical properties of wood, metal, or skin. You could make sounds that had never existed before.

Early adopters — Wendy Carlos, Keith Emerson, Kraftwerk — didn’t just use synths to imitate existing instruments. They used them to imagine new worlds. Sci-fi film scores, shimmering ambient textures, robotic basslines — the future had arrived, and it was wired.

By the 1980s, synths had gone mainstream. You couldn’t walk through a shopping centre without hearing a Yamaha DX7 patch echoing off the tiles. Meanwhile, the Roland TR-808 drum machine, released in 1980, was quietly reshaping the foundations of pop, electro, and hip-hop. It’s hard to imagine Marvin Gaye’s “Sexual Healing”, Afrika Bambaataa, or early Kanye without it.

And all of it was machine-made.

💡 ARTMASTER TIP: Synths and drum machines gave artists new creative tools — but it’s what they did with them that made the hits. For a look at the wild, often surprising methods songwriters use to spark ideas, check out 14 songwriting techniques used to craft hits.

MIDI: the unsung hero of modern music

Now, here’s the bit casual music fans tend to miss—but musicians, producers and engineers will tell you: MIDI changed everything.

In 1983, a miracle happened. Competing instrument manufacturers — Yamaha, Roland, Korg, Sequential Circuits — sat down and actually agreed on something: a common language for musical gear. This was MIDI: the Musical Instrument Digital Interface.

In 1983, a miracle happened. Competing instrument manufacturers — Yamaha, Roland, Korg, Sequential Circuits — sat down and actually agreed on something: a common language for musical gear. This was MIDI: the Musical Instrument Digital Interface.

Before MIDI, electronic instruments didn’t play nicely together. Now, you could connect a keyboard to a drum machine, a sequencer, and a computer—and they’d all stay in time. One device could control another. Notes, pitch, timing, even modulation could be sent as data.

And the data was light. You could save entire performances as a string of instructions, not audio files. A whole song could fit on a floppy disk — and be edited, rearranged, or re-performed instantly.

If synthesizers gave music new sounds, MIDI gave musicians control. It was the brain behind the bleep.

DAWs: the studio moves into the bedroom

Then came the biggest shift since Edison’s wax cylinder: the Digital Audio Workstation, or DAW.

In the 1990s, software like Pro Tools, Cubase, and later Logic and Ableton Live, turned computers into full-blown recording studios. You could now record, edit, mix, and master an album entirely inside a laptop.

In the 1990s, software like Pro Tools, Cubase, and later Logic and Ableton Live, turned computers into full-blown recording studios. You could now record, edit, mix, and master an album entirely inside a laptop.

Gone were the days of booking studio time or rewinding reels. You had infinite tracks, unlimited undo, and plugins that emulated everything from vintage tape saturation to grand pianos recorded at Abbey Road. What once required a mixing desk the size of a dining table could now be done on a sofa, with a mouse.

More importantly, it meant that anyone with time, talent, and a decent computer could make a record. You didn’t need a label, a budget, or even a band. Just ideas, software, and stubbornness.

This was the democratisation of music production, and it birthed an entire generation of bedroom producers, YouTube artists, and indie stars who could compete sonically with the big players — because they had access to the same tools.

💡 ARTMASTER TIP: Want to turn your ideas into a fully produced track with just a few plugins? Our ultimate guide to VST plugins covers the best synths, drums, effects, and more — free and paid.

The MP3 and the disintegration of the album

Around the same time, MP3s entered the chat. A marvel of audio compression, the MP3 could squash a song down to a tenth of its original size. Audiophiles moaned, of course, but the rest of us were too busy burning CDs, sharing files on Napster, and loading up our iPods.

Music became portable, shareable, and most of all, detached from format. The tracklist was no longer sacred. Albums became shuffled playlists. Attention spans shrank. Songs had to hook you in 8 seconds or you skipped to the next one.

Music became portable, shareable, and most of all, detached from format. The tracklist was no longer sacred. Albums became shuffled playlists. Attention spans shrank. Songs had to hook you in 8 seconds or you skipped to the next one.

Later came iTunes, then Spotify, and suddenly, we weren’t owning music—we were renting it.

For artists, this was a mixed blessing. The barriers to entry vanished — but so did the paychecks. Streams pay in fractions. But reach? Instant. You could be recording in your bedroom on Monday and added to a playlist with 10 million followers by Friday.

Virtual instruments: orchestras in your laptop

Once upon a time, if you wanted strings on your track, you had to hire string players. If you wanted a horn section, you needed a few brass players and a studio that didn’t smell like damp carpet.

Not anymore.

With modern sample libraries and virtual instruments, you can now load up an entire orchestra — violins, oboes, timpani and all — and play it with a keyboard. Want a jazz trio? A pipe organ? A South Indian percussion ensemble? There’s a plugin for that.

With modern sample libraries and virtual instruments, you can now load up an entire orchestra — violins, oboes, timpani and all — and play it with a keyboard. Want a jazz trio? A pipe organ? A South Indian percussion ensemble? There’s a plugin for that.

And it’s not just quantity. The quality is often astonishing. Developers spend years recording every nuance of every note, at every velocity, on every articulation. Bowed, plucked, staccato, legato — it's all there. The software doesn’t just mimic the sound — it mimics the behaviour.

Of course, it’s not the same as the real thing. It’s never quite as unpredictable or as gloriously messy. But for most producers, composers, and hobbyists, it’s close enough to bring their ideas to life. And crucially, it puts world-class tools into the hands of people who, just a few decades ago, wouldn’t have had access to them.

💡 ARTMASTER TIP: Orchestras used to take budgets and booking agents — now they fit inside a plugin. Want to explore the best of them? Start with our top VSTs for orchestral music.

The machines get clever: here comes AI

And now we arrive at the present — and the part that tends to make people nervous.

Artificial Intelligence is already being used to write songs, generate melodies, finish chord progressions, analyse vocal takes, and even give instrumental feedback. It’s being trained on everything from Bach to Beyoncé, from jazz improvisation to EDM drops.

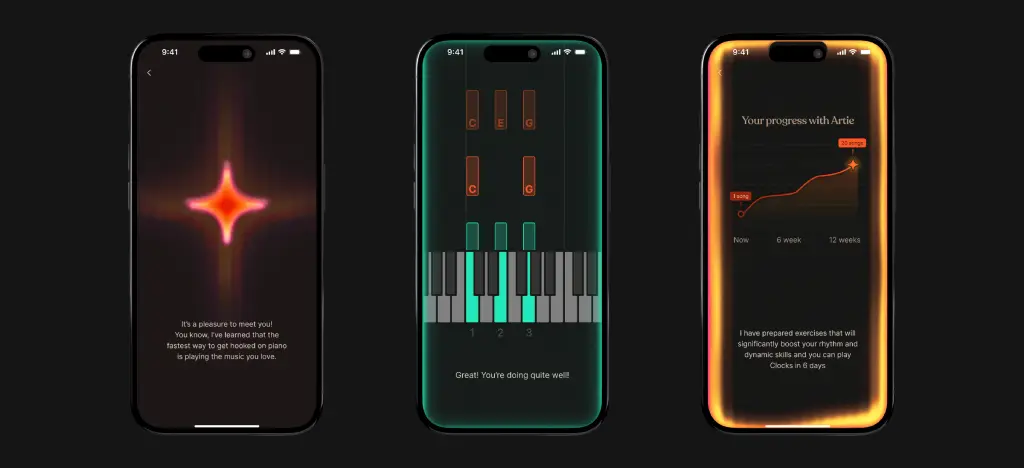

Some tools, like the one we’re building at ArtMaster, go further — not just generating music, but teaching it. Real-time feedback. Custom exercises based on how you play. Guidance that adapts with you, rather than repeating the same page from a grade book.

Some tools, like the one we’re building at ArtMaster, go further — not just generating music, but teaching it. Real-time feedback. Custom exercises based on how you play. Guidance that adapts with you, rather than repeating the same page from a grade book.

To some, this feels like the robots are replacing the teachers. But that misses the point. The best AI tools don’t replace creativity — they amplify it. They offer access, insight, and encouragement. They remove some of the friction that stops people from making music in the first place.

And if history has taught us anything, it’s this: every time a new music technology comes along, someone says it’s the end of “real music.” And every time, musicians prove them wrong by using it to create something new.

💡 ARTMASTER TIP: For a glimpse at how AI is already changing the way we learn, create, and connect with music, check out AI music revolution: the tools reshaping how we learn, create & experience music.

So — where does this all leave us?

If you strip it back, music technology has always been about solving problems:

How can I play louder?

How can I record this and hear it later?

How can I do this without needing a full band or a big budget?

How can I express what’s in my head — even if I don’t know how to read music?

From the first bone flute to the latest DAW, every step has been about expanding the boundaries of what’s musically possible.

Sure — machines can now write melodies, correct timing, even improvise. But they don’t feel heartbreak. They don’t get goosebumps. They don’t write lyrics at 2am because they can’t sleep.

You do that.

The machines are brilliant — but they still need us to tell them what matters.

Learn music technology

Whether you’re layering a string section with sample libraries, shaping lyrics into songs, or building your first home setup, today’s music tools make it all possible — and accessible.

If this article has sparked ideas, here are three brilliant places to start:

🎼 Want to create sweeping, cinematic sounds?

Explore professional orchestration and production in our Orchestral Music Production course with Alex Moukala.

✍️ Got a melody stuck in your head?

Turn it into something real with Printz Board's Songwriting course (Black Eyed Peas), packed with creative techniques and tools to help you write a complete song.

🎚️ Curious about recording from home?

Build your setup and learn to produce with confidence in our home recording course by Grammy-winner Chris Kasych (Adele)

Try them all FREE for 7 Days